Author: Mariusz Patelski

The history of Poland – particularly that of the 20th century – saw no shortage of courageous women who fulfilled their patriotic duty towards their home country either on the battlefield or underground. Scouts, members of the Polish Military Organisation and the Military Women’s Service, as well as ordinary women acting in wartime circumstances, often undertook tasks which more than one man found hard to deal with. That group included Cecylia Jordan Rozwadowska from Lwow, an officer in the Home Army (AK) and the main organiser of cultural and educational activity at the prisoner-of-war camp in Oberlangen.

Cecylia Jordan Rozwdowska was born in Lwow on 15th January 1903. She was the daughter of Jan Emanuel Jordan Rozwadowski and Maria nee Jordan Rozwadowska (a marriage of cousins). She came from a landed gentry family with great patriotic traditions; her forefathers took part in most of the Polish uprisings and wars during Poland’s partitions, her uncle (her father’s first cousin) – General Tadeusz Rozwadowski playing a significant role in the battles for the independence of Poland in 1918-1920. Her father Jan, had a great influence on her upbringing and views. He was assistant professor in Political Economics at Lwow University, a landowner, outstanding politician of the National Democratic Party, close associate of Roman Dmowski, co-organiser and secretary of the Polish National Committee in Paris. Cecylia had seven siblings: Stanislaw, Maria, Janina, Mieczyslaw, Zofia, Franciszek and Wincenty.

She spent her early childhood in Babin, the Rozwadowski family estate near Kalusz. After the beginning of the Ist World War, Jan Rozwadowski and his family left Galicia for Switzerland in mid-1915 for political reasons. Due to their father’s political activities and hence frequent absence, Cecylia and her sister Janina were sent to the exclusive French Catholic boarding school (Academie St. Croix, Fribourg). The choice of town was probably not accidental as that was where the Publishing Committee of the Encyclopedie Polonaise worked, Jan Rozwadowski being its vice-chairman. In summer 1919 Cecylia and her family were in Paris where delegates were taking part in the Peace Conference. In her passport she was described as being blonde with hazel brown eyes, fair eyebrows and of medium height. Both her father, Jan and uncle, General Tadeusz Jordan Rozwadowski played active roles in the work of the Polish delegation. That year Cecylia’s mother, Maria died in Paris. Therefore, Cecylia partly took over the role of mother towards her younger brothers, Franciszek and Wincenty.

Dzieci Jana Rozwadowskiego. Od lewej Cecylia, Janka, Mieczysłąw, Zofia, Franciszek,Lozanna 1917 r.

After finishing school in Fribourg in 1921 Cecylia returned to Poland and after taking extra lessons in History and Polish Literature, passed her matriculation examination in Lwow at the beginning of 1922. She continued her education at the National School of Industrial Design in Krakow (1922-1925). The director of the school was the famous sculptor, Jan Raszka and Cecylia’s teachers included the following professors: Andrzej Oles, Waclaw Krzyzanowski, Stanislaw Wojcik, Karol Homolacs and Jan Bukowski.

She attended lectures by Jagiellonian University professors, including classes on the theory and history of art run by Stanislaw Noakowski and Julian Pagaczewski as well as linguistics by Jan Michal Rozwadowski. Meetings with Noakowski and Pagaczewski had a significant influence on her artistic views. Being sensitive to poverty among the academic youth she used her father’s influence to help poorer students. She tried to support the Paris Committee whose aim it was to send students of the Krakow Academy of Fine Art on scholarships to Paris. This was partly connected with the activity of the painter and professor at the Academy of Fine Art, Jozef Pankiewicz who opened a Parisian section of the Krakow Academy of Fine Art in 1925.

During her studies, following family tradition and her father’s wish, Cecylia belonged to the Krakow branch of the Academic Union of All Poland Youth and in April 1923 she took part in a reunion of the organisation in Poznan. According to letters written to her father, she preferred the company of intelligent, yet poorly dressed academics to the snobbish aristocrats she met in Krakow salons speaking French with a Parisian accent. However, her political convictions at the time did not appeal to all members of her family, particularly her uncle Tadeusz Rozwadowski. After lunch spent in the company of the general and his wife as well as Jadwiga Komorowska (the sister of the future general, Tadeusz ‘Bor’ Komorowski) at the theatre, Cecylia wrote to her father that her uncle: “complained about the National Democrats and called me a fascist but was as charming as ever..”

While studying in Krakow Cecylia made posters advertising art exhibitions and designed furniture. After finishing the Krakow school she continued her art studies in Paris and Rome as well as the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art. Her strong personality and independence yet very delicate and sensitive nature made her stand out considerably from her contemporaries from the landed gentry manors. She preferred travelling, hunting, horse riding, bull fighting in Nimes, riding competitions in Rome or experimental films in Paris to the life of a staid wife. She loved France, its culture and history. Personally meeting Marshal Ferdinand Foch (who had conquered the German Army during the 1st World War) in Krakow in 1923 was a special experience for her. While in Krakow she broadened her knowledge of Romance literature, attending lectures by Professors Wladyslaw Folkierski and Stanislaw Wedkiewicz. Her frequent trips to France were also connected with the fact that her sister Janina had settled there having married a Frenchman, Jean Filliol.

Despite her love of travelling she gladly returned to her native Lwow and family home at ulica Clowa 3, a villa belonging to her father since the early 1920s. The building was unusual in that it resembled a country residence rather than a typical house belonging to the Lwow bourgeoisie. Stanislaw Makowiecki, a friend of Cecylia’s brother, Mieczyslaw Rozwadowski described the Rozwadowski home: “at ulica Clowa 3 stood – sideways to the street – the Rozwadowski family house. The gate led to a triangular shaped garden from which you entered the house under four columns as if entering a country manor. Visitors were welcomed into the sitting room on the first floor. There were sofas, armchairs, bookshelves, a piano, my favourite instrument.. The furniture was laid out in such a way that several conversations could take place at one time which was very pleasant during larger encounters. On the small tables lay French newspapers. When Pan Jan, Miecio’s father would leave I would sit down to the piano. Everyone loved Russian romances and Miecio adored Wertynski, a very popular singer in Poland and sang Kominek zgasl, Utro tumannoje, Ugololok etc. Miecio’s family consisted of his father, who had taken part in the Parisian negotiations with the allies and was then director of a bank, his second wife, sisters, the kind and serious Janka, lively and pretty Cesia – the artist and younger brothers Wicek and Franio whom I took little notice of at that time.”

That house was where family reunions took place as well as meetings between outstanding representatives of the national movement. Roman Dmowski would stay there when in Lwow, particularly after 1926 during the building of the Large Poland Camp. There was a close friendship and understanding between Cecylia and her father until his death in 1935, despite her abandoning national-democratic convictions in adulthood.

Rodzeństwo Mieczysław i Cecylia Jordan Rozwadowscy, lata trzydzieste

In the 1930s Cecylia moved to Warsaw where she devoted her attention to industrial art. She stayed at the Hotel Seymowy, having been helped by her long-time friend Martyna “Tychna” Puzynina (nee Gryglaszewska) and husband Stefan Puzyna. At the time, Martyna Puzynina – a doctor in Anthropology from the University of Lwow was an assistant at the Faculty of Anthropology in the Central Institute of Physical Education in Warsaw.

The 1st of September 1939 found Cecylia in the capital. As she wrote, with the outbreak of war she exchanged intellectual Athens for martial Sparta. A well-known pre-war painter, Irena Borowska-Pokrzewnicka recalled how during the time of the defence of Warsaw, “in the hellish fire of enemy attack Cecylia would go backwards and forwards across the river to Praga for food and bandages etc. for the wounded lying on the floor of the Bristol hotel restaurant.”

Cecylia experienced a severe blow at the very beginning of war with the death of her brother Mieczyslaw. He had begun his studies at the Technical University in Lwow. After the May 1926 coup he moved to France where he continued his studies at the elitist air school Supaero – Ecole superieure d’aeronautique et de constructions mecaniques. On 31st August 1939 he was called up to the air fields in Warsaw and joined the reserve squadron of the Ist Air Regiment. Due to an insufficient number of aircraft for the mobilised pilots they joined the infantry. Towards the end of the 1939 campaign, they joined the Independent Operations Group “Polesie” under the leadership of General Franciszek Kleeberg. Mieczyslaw was killed in battle on 2nd or 3rd October. In unknown circumstances Cecylia heard about the death of Mieczyslaw and managed to get to Kock in October where she identified her brother’s body by his wedding ring.

After the beginning of the occupation the painter took part in the resistance. According to her cousin, Felicja Zeromska (unconfirmed information) “Rozwadowska belonged to the closest milieu of General [Tadeusz] Bor Komorowski.” In 1943 Cecylia experienced another blow when the gestapo arrested Martyna “Tychna” Puzynina who, after the beginning of the occupation, first Soviet and then German, had been an inspector in the Lwow Section of the ZWZ-AK (Underground Union for Armed Struggle – Home Army). In March 1943 Tychna , as a result of betrayal, was imprisoned and after an exhaustive investigation was sent to the concentration camp in Auschwitz. There, due to her education she was forced to work in the hospital alongside Dr. Mengele – “The Angel of Death”. During her time in the camp Puzynina made clandestine notes of the criminal research carried out by the German doctor on camp prisoners. After the war those materials reached Cardinal Adam Sapieha and after that they were sent to the Main Committee for the Investigation of Nazi War Crimes. Proof of that unique friendship and separation caused by prison, was a poem entitled “Paczka” (Packet) written by Cecylia in 1943 and dedicated to Tychna:

Deutschland – Auschwitz – Oberschlesien

(hard to write these heresies)

Frauenlager Postam Two –

And the war goes on and on…

The surname below, beloved name,

Birthdate revealed

And the new name you now hold:

Gefangennummer four hundred and thirty eight.

Block 22. On the left side

Inhalt carefully arranged.

Pedantically provided weight –

yet all is lies and mockery.

Because I lie about the bread and butter –

I send you faith in a piece of paper.

(…)

When you unfold this contraband,

You’ll understand that you will not perish.

I’m sprinkling Vitamin C for you everywhere:

Perhaps there will be too much of it?

If so – please, forgive me –

That is my heart smashed to powder.

With the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising Cecylia was assigned to the quartermaster of sub-division “Bogumil”, in sub-district Slawbor, 1st Division Radwan. Under the pseudonym “Barbara” she led the girls’ division helping Warsaw’s civilian population. For her work at that time she was awarded the Krzyz Walecznych (A Polish cross awarded for wartime bravery).

With the capitulation of Warsaw platoon leader Cecylia found herself in a German prisoner- of-war camp. With a group of women – AK soldiers on 11th October 1944 she landed in stalag XB in Sandbostel. Initially she was in barracks 90 and on 1st November was moved to the large barracks called Aufnahme. Rozwadowska wrote about her camp experiences in her fascinating diary which was later published in the London Wiadomosci and Wiez in Poland. Cecylia wrote: “I am now KGF (Kriegsefangen) No. 224513. My kennkart is very torn and in fact goes on record, and my only passport is this number, which in the event of death gets cut in two, one half of it goes into the earth with the dead body and the other goes on record with the documents.” In the camp the AK girls met Polish prisoners-of-war – soldiers from September 1939. That meeting made an enormous impression on both sides. Cecylia wrote: “Looking at them, at their surprised and sometimes frightened expressions in our direction, all of a sudden I fully understand what these 5 years of occupation have done to us, plus two months in the Uprising. 5 years spent on the streets. Everyday life and that of the family and home was almost dead because in order to survive you had to buy and sell in bars, shops and in the street. That has had an effect on our manners, our language, on everything. We are no longer refined women. The abnormal yet wonderful Uprising life of the past two months has completed that task. Those poor cadet officers pined after their country for 5 years, for that idealized Polish woman and all of a sudden they saw a band of swearing ragamuffins wearing trousers… In spite of that they are the best and kindest, not saying a word to us of their consternation… Life is beautiful and full of unexpected surprises. This evening I saw a young couple in the corridor: a cadet was looking, madly in love, into the blue eyes of a young Varsavian woman dressed in rags”.

Cecylia’s diaries also contained very critical words about the very sense of the last Uprising, no doubt dictated by the rancour of defeat. ”Oh God, cure us once and for all from sudden, romantic outbursts and romanticism in general. I loathe more and more our futile heroism. What I want for us in the future is maturity and reason. I don’t want common sense or the French bon sens, but what I want, desire and pray for is wisdom. I don’t want courageous mothers to send their sons to a certain, pointless and stupid death. I want them not to cry when their sons die for a wise idea. Mothers must demand wisdom from their sons, not constant bravery. Dying is not an art, living is.. I remember that concierge sweeping the stairs in ulica Krucza during the Uprising and that inhuman bombing, who asked me: ‘How are things, Madame?’… I replied: ‘all is well’. He shook his head sceptically and said: ‘No, all is not well, no, because we do not have any heads but we always have sabres and that horrifically cheap blood.’… And he continued sweeping the stairs, deep in thought, with the planes flying overhead. I am now learning to appreciate Dmowski more and more and I admire him without reservation. That man despite our romanticised society begged for rationality, for doing away with romanticism in politics. Everyone was against him, now after the recent Warsaw event there is sobriety – I notice a great return to Dmowski among wide groups of young girls, consideration among adults. (…) We began during the time of Kosciuszko with scythes against cannon and we are ending today in Warsaw, where we had bottles with petrol against tanks, and prayers to God against the aeroplanes. Where, after our desperate calls for help to our allies (we’re always begging the allies for help), we watched our boys who were well armed in superb planes fighting in Normandy, Belgium and Holland while Warsaw was dying without a trace of assistance. And all that due to romanticism, i.e. stupidity. I cannot write about this, I am so very angry and desperately helpless.”

In the stalag, platoon leader Rozwadowska embarked on cultural and educational activity, lecturing on the theory and history of art, referring among others to Noakowski and Pagaczewski. After the departure of the women officers to the offlag, she temporarily took over the command of the Aufnahme barracks.

In December 1944 she was moved with other women non-commissioned officers to stalag VI C in Oberlangen. Conditions in that camp were very bad. This is how Irena Szkrzynska described it: “The camp in Oberlangen had a very black past. It lay on the marshes of Emsland, in north-western Germany, it was one of the numerous concentration camps which had been established in the years 1933-1938 for opponents to Hitler’s regime. During the 2nd World War some camps were taken over by the Wehrmaht and prisoners-of-war as well as soldiers from the occupied countries in Europe were interned there. The harsh climate, slave labour, hunger and illnesses meant that it became an extermination camp. In October 1944 Stafflager VI C in Oberlangen was deleted from the register of prisoner-of-war camps due to its totally unsuitable living conditions. The International Red Cross in Geneva was unaware of the fact that Polish women prisoners-of-war had been interned there. The Germans considered Oberlangen to be a penal camp and that is where they grouped the Polish AK women as a rebellious, unruly group because we refused to work as civilians in the German war industry. The conditions under which we had to survive the winter of 1944/1945 were very hard to bear. Rotting, wooden barracks with windows and doors which did not shut, rooms holding 200 people with 3-level bunk beds, very thin mattresses, 2 iron heaters in each barracks heated with wet turf, which provided more smoke than heat. In one barracks there was a row of metal troughs with trickling water (if any water at all) and behind it a couple of primitive latrines, such were the entire toilet facilities.”

In her new prison Cecylia joined the Instructors’ Council. Together with Captain Halina Jablonska-Ter-Oganjan, Alicja Kadler, Janina Skrzynska, Zofia Trenker and Captain Janina Tuwan she was responsible for culture and education in the camp. According to numerous fellow prisoners, due to her age, experience and predisposition, Rozwadowska did indeed become the main organiser of cultural and educational life in Oberlangen, acquiring the unofficial title of “Minister of Education”. Alina Szeppe-Kamienska-Karbowska wrote: “If not for Cecylia and a few others there would be nothing here. Her energy and capacity for singling out talents is the basis (…) of cultural life”. It was further to Cecylia’s initiative that the imprisoned women set in motion Camp University lectures. Initially, due to lack of space they were repeated in different barracks. It was not until March 1945 that barracks no. 11 was allocated to the Ministry of Education. That was where lectures, concerts and recitals took place. The topics included: ancient history, medieval history, history of Poland and various other subjects.

This is how Cecylia described the educational service in the camp: “I am the education officer for the entire five-barracks camp (i.e. 1000 women). I’m running a series of art lectures. I started with a lecture about art in general and an introduction to Greek Art. Waleria, a classical philologist gave the second lecture, Helena Karbowska spoke about Greek Sculpture and then about “a trip around Greece, Paestum and Sicily”, then Renieta spoke about Sparta and Helena Zelwerowicz about Greek philosophy. The following subjects are being prepared: Greek literature, Greek history, Greek theatre, Ancient law and following through to the Middle Ages. Language courses are also taking place. The result is that my barracks gives me tremendous pleasure. In one corner I see a meeting of a poetry group discussing the contents of the first issue of a newspaper, on my desk I have a few guild hymns to guild patrons. In another corner the metal guild is working on the design of cups, saucers, ashtrays, guild crests, some of them are working on a dress for Our Lady of Czestochowa. In the third corner I came across 9 philosophers in a heated discussion about Plato’s influence on Christian religion, and Aristotle through Saint Thomas Aquinas. There’s no way back…. Things are running amok. I have absolutely no time for anything.”

Cecylia Rozwadowska personally ran the following lectures: “The Definition of Art” and “The Art of Greece” as well as “Art in the Middle Ages”.

Thanks to Cecylia and her co-workers the following were organised: a grammar school course for girls and vocational courses. Lectures took place at university level, language courses (most people enrolled on the English course), arts and culture classes (literary evenings and art workshops, including making objects out of food tins.) Cecylia, Maria Mirska, Jolanta Netto and Irena Sluczanska were in the editorial team of a ‘live newspaper’, the contents of which, due to lack of paper was read out in one barracks after another and in the hospital. The first two issues appeared in January 1945 and then after a brief interval in March 1945 the paper was continued under the name “Camp radio”. Cecylia wrote introductory articles, the purpose of which was above all to boost the morale of the girls who felt lost in the world of the camp and were separated from their families. The titles of those texts do not seem accidental: “About optimists” (18 III 1945), “About the Polish woman” (25 III 1945), “About endurance” (18 III ?) and “About battle” (8 IV 1945).

On 12th April 1945 stalag VI C Oberlangen was liberated by a patrol of the 2nd armoured regiment under the command of Lieutenant Stanislaw Koszutski, which was part of General Maczek’s 1st Armoured Division. It is worth remembering that Cecylia’s brother, Franciszek Rozwadowski served in that division as did her two first cousins Lieutenant Wiktor and Captain Jan Rozwadowski. The liberation of the camp was a moving moment for the women, both Polish prisoners-of war and foreign soldiers. A few hours later a rather humorous scene took place in the headquarters of the 1st Canadian Army: Dick Payan, an officer responsible for the supply of ammunition received an unusual order from Joe Sarantoso, his counterpart in the 2nd corps HQ. J Williams recalled years later how conversation in the HQ quietened down when Dick Payan received a report over the phone: “ Yes, I understand, Joe. Please repeat the first point. 250 bras?” That was the beginning of a long list of items of underwear, clothing, bedding etc. which were hard to come by in a field army which was a long way from its hospitals. When he put the receiver down, someone asked “What was that, Dick?” Payan’s friendly face expressed surprise bordering on disbelief. His eyes were shining. He blew his nose and said: “The Poles have taken over the concentration camp, where there are many Polish women, some of whom are the wives and daughters of the Division’s soldiers”.

In the 1st Division the liberation of the Oberlangen camp was considered as one of the most significant moments in the unit’s history, which General Maczek emphasised in his memoirs. After liberation, Second Lieutenant Cecylia Rozwadowska (officer’s rank manifested and verified after liberation) continued working as education officer among former women prisoners-of-war who were moved to slightly better conditions in the neighbouring camp in Niederlangen That camp was transformed into the Military Centre Niederlangen V and later Military Centre no. 102 in Hange. Those places were part of German territory now under Polish occupation of the 1st Armoured Division with their main centre in Maczkow.

Liberation did not solve all the problems of the women-soldiers. Many of them complained about difficult living conditions in the camp, lack of activity and education possibilities and not even having access to the Polish press or books. A Polish war correspondent, Zygmunt Nagorski appealed to the Polish authorities to give immediate attention to the fate of those women, particularly the youngest of whom should be sent to schools or vocational courses. That problem was also given priority by the Division’s High Command particularly due to concern about demoralisation. Colonel Bronislaw Noel who was in charge of former Polish prisoners-of-war wrote in a report dated 28th May 1945: “The AK women from the camp in Niederlangen have high civic values but only a few of them work for the Division. The majority are inactive, give in to the temptations of light-hearted play and activities, consequently becoming depraved. A shameful role of guardians-seducers is played by the British and, also, unfortunately the Poles. Clearing the camp, a suitable way of making use of and educating the female youth is a matter of great urgency.

It was not accidental that Cecylia Rozwadowska’s main duty at that time was enabling young girls who had been liberated from the camp to continue their education in West European schools and universities. Her fluent knowledge of German, French and English as well as her numerous pre-war contacts in France helped Second Lieutenant Rozwadowska in that work. In her mission she could also rely on the help of her brother, Lieutenant Wincenty Rozwadowski – an officer in the Polish intelligence network in France (pseudonym Pascal – head of intelligence operations in the so-called “F-2” Agency), who also had numerous connections among the European aristocracy and bourgeoisie. It was probably to do with those duties that she joined a delegation which travelled to Paris at the turn of May and June 1945.

In September 1945 Cecylia took three months’ sick leave from which it appears she did not return to Niederlangen. She had to stop further service due to stomach cancer. Worn out by overwork and harsh conditions in the prisoner-of-war camp she could not endure the hardship of illness. On 8th June 1946 after struggling for six months Cecylia Rozwadowska died at the Croix Rouge hospital in Passy, Paris. She was buried at the Batignolles cemetery in Paris beside her mother, Maria Rozwadowska.

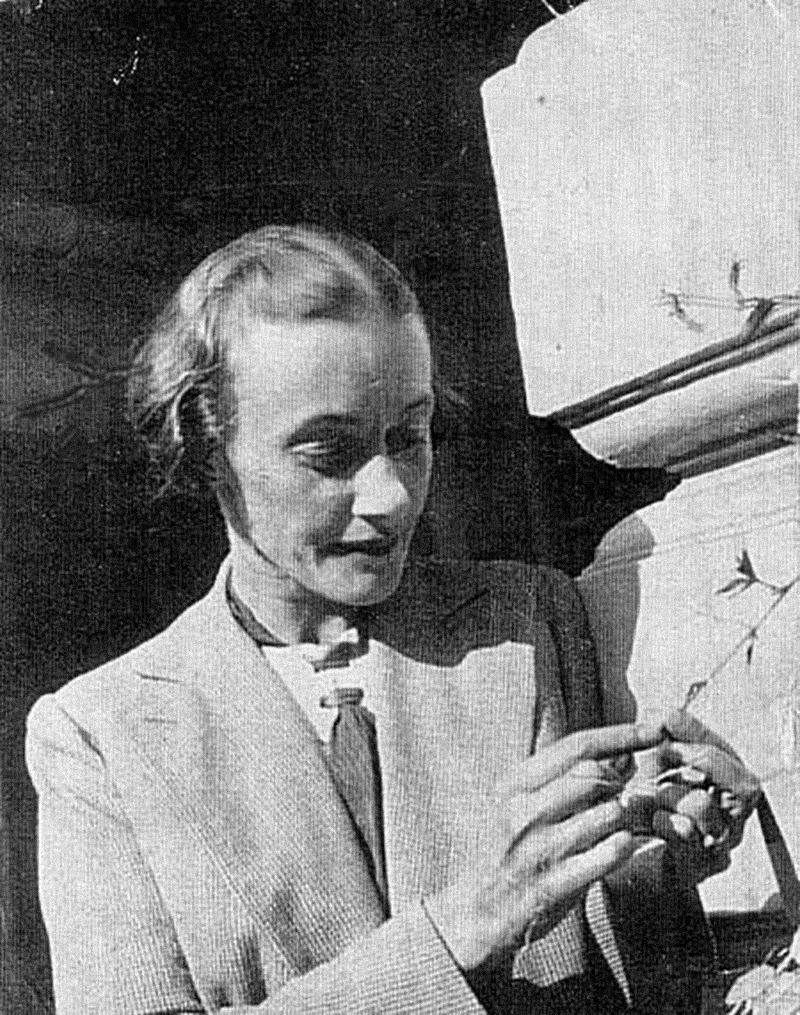

Cecylia in 1946 (?)